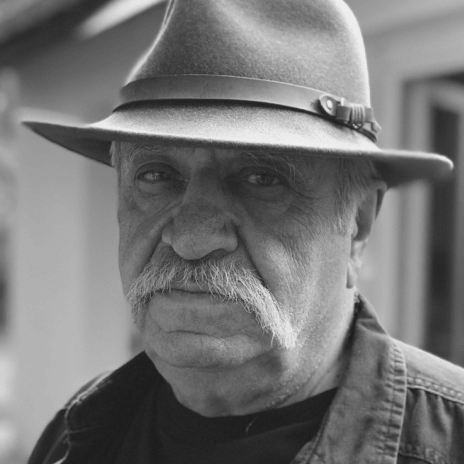

Albert Avetissian

installed in cities in Armenia, Ukraine, Russia, and France. Avetisyan’s works are exhibited in museums, and have been part of many exhibitions organized in Yerevan, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Aleppo, and Paris. Avetisyan has taken part in more than 60 exhibitions altogether.

Besides his professional qualities, Albert Avetisyan also has rare stamina. He is interested in everything: archaic forms, reliefs, and ancient art. National traditions never served as an end in themselves for Avetisyan, although the artist has created sculptural portraits of Marshal Khudyakov, John Kirakosyan, General Amatuni, and others, all of which are notable for their individuality.

Albert Avetisyan’s works are meant most of all for concentrated, unhurried viewing, and games of the imagination. Their originality is clear even to people who aren’t artists themselves. The sculptor is quite exact in the way he transfers characters and movements through details and facts. It looks as if his sculptures are small novellas, parables, or myths which express their creator’s feelings and thoughts to a full degree.

Together with the sculptor Frid Sogonyan, Albert Avetisyan created a 350-ton bronze monument entitled “Forced Crossing of the Dnepr” for a memorial in the State Museum of Ukraine. This monument is the only one like it in the world. In 1988 Avetisyan created the sculpture “Birds”, which is dedicated to the victims of the Spitak Earthquake. The sculpture is situated in the French city of Issy-Les-Moulineaux. Avetisyan also created a bas-relief for the Ceremonial Hall of the Armenian Educational Institution “Saint Mashtots” in the French city of Alfortville. This sculpture features Armenian cultural fi gures such as Movses Khorenatsi, Anania Shirakatsi, Mkhitar Heratsi, Mkhitar Gosh, Toros Roslin, and Momik. This work was a gift from the Armenian

sculptor to the educational institution.

Albert Avetisyan’s works of recent years penetrate into the depths of man’s inner world, opening dramatic feelings of love and delight. Such works include the bronze sculptures “Amazon”, “Sister of Chairty”, “Motherhood”, “My Muse”, “Komitas”, “Madame Butterfl y”, and “Zhanna Simonyan”, all of which show the movements of the author’s thoughts and soul.

Albert Avetisyan and his wife, the artist Zhanna Simonyan, have been living in France since 1999. Today the couple holds already traditional exhibitions named “Family of Artists”. These exhibitions feature the sculptures of father and son — Albert and Arsen Avetisyan, and the oil paintings of the artist Zhanna Simonyan. In 2004 the family happiness of Albert Avetisyan and Zhanna Simonyan was destroyed by a catastrophe: their only son, Arsen, was killed in a car accident together with his family. The obituary reads: “The sculptor Arsen Avetisyan, a man of

rare and great talent, with a glorious and good nature, has died. Fate gave him only 33 years to live – so little, so sparing, but he lived them fully and fruitfully.

Arsen indefatigably created beauty, and his energetic, fiery exhibitions will be remembered for a long time, as will his world of wonderful images. This world will live inside us, winning over connoisseurs of the beautiful with its originality, elegance, and dynamism".

WHAT DOES ALBERT AVETISYAN’S ART SAY?

Throughout history artists have used their art to speak about those subjects which are most important to them in life. For example, in the Paleolithic age man not only painted oxen and deer on the walls of deep caves, but also made stone fi gures representing goddesses-protectors. Paleolithic man did so not as a form of entertainment, and not so as to decorate his home, but rather out of necessity: he understood that his tribe wouldn’t survive without the patronage of the goddesses. That’s why even to this day, after many tens of millennia, these ancient stone goddesses with hypertrophied female forms bring us the energy of power and belief. The bronze fi gures made by Albert Avetisyan in the ХХ–ХХI centuries are infi nitely far away from the Paleolithic Venus in terms of their graceful plastics and elegance. The perfect forms and beautiful poses of Avetisyan’s sculptures are both refi ned and aristocratic. That said, at the same time, Avetisyan’s fi gures often have no face, just like their distant stone predecessors. Either that, or the faces are generalized to such a degree that the viewer gets a clear message: most likely the sculpture is not the portrait of one person, but rather a more global subject. This subject, of course, is beauty — that very beauty which, in the words of one great writer, can save mankind. This will be done in the same way that at one time the strength of the protector goddess saved ancient man. And in this way Albert Avetisyan is a direct successor of the many-century tradition of human creation. Today one can see the artist’s particular boldness in his fearlessness before beauty and perfection of form. And there is no need to speak of the relativity of these concepts — they are absolute for Albert Avetisyan. The harmony of lines and volumes reached in his work most often gives birth to the female fi gure. In this way the sculptor follows not only the examples of antiquity and the renaissance, but also his own temperament — creative and human. Here we can clearly see discoveries, but the searches made by the sculptor are hidden. Avetisyan’s sculptures don’t carry signs of the sculptor’s labor, of the poignant movement to the only possible and most beautiful variant of the form. These forms seem to have arisen by themselves, lightly and freely — like Aphrodite from the foam of the sea. But that’s only upon fi rst glance. Upon a more thoughtful analysis one understands that the projects’ subjects and their plastics feature the history and experience of world culture, as well as the highest quality professionalism. “Theft of Europe” is a reference to ancient mythology and to the modern history of Russian art. The delicate strengthening of characteristic traits of the image — the speed of movement, the touching contrast between the powerful head of the bull and the fragile fi gure of the girl, as well as the underlined fragmentariness of the imagery — all of these speak to the artistic tact of a master and of his confi dence in his own abilities. Furthermore, these traits speak of a feeling of inner freedom which is necessary for any artist, when the artist not only can, but must do only that which he wants, and that which he considers to be necessary and interesting. And in this case he won’t be afraid of dialogues with great predecessors. He speaks with them on equal footing, like one master with another. Albert Avetisyan is often, and not without reason, called an erotic sculptor. And in this sense the sculptor is courageous as only a real professional can be, taking risks, but at the same time feeling confi dent of victory. Danger, in this case, doesn’t come from the possibility of being accused of looking for simple paths to modest viewers’ hearts. Rather, it comes from the possibility of not being able to keep the extremely unstable balance between sensitivity in each concrete sculpture and the necessary “detachment” which makes this sculpture a work of art. What is the purpose of this risk? Evidently, its purpose is to overcome hypocrisy and vulgarity, debauchery and boredom. This risk is necessary for preserving true and lofty beauty, the powerful and vital beauty of unending life. “Leda and Cygnus” is a clear example of such a sculpture “on the verge of a foul”. The subject of the love between the beautiful Leda and Zeus, who seduced Leda in the form of a swan (the beautiful Helen, the reason for the Trojan War, was born from this love) has excited artists’ imagination for a long time. But the expression and openness of Albert Avetisyan’s sculpture goes beyond the borders of the mythological story, turning into a generalized image of sensitive passion. The sculptor managed to fi nd such means of expression and such methods of form which make the erotic scene a symbol of great love. A conversation about love in its most concrete and most exalted meaning is present in each work by Albert Avetisyan. Love, just like beauty which saves the world, is an eternal theme in art. Probably the world will collapse just as soon as the last artist speaking of love passes away. Albert Avetisyan is one of the bold spirits who is brave enough to speak of this love passionately and convincingly.

Elena Tyunina, Art historian